The Genealogist’s Internet

The Genealogist’s Internet |

Indexes, transcriptions and images

The core of any family history research in the British Isles is the information drawn from the registrations of births, marriages and deaths over the last 170 years, and from the records of christenings, marriages and burials in parish registers starting in the sixteenth century. Linking these two sources are the census records, which enable an address from the period of civil registration to lead to a place and approximate year of birth in the time before registration.

The three following chapters examine online sources for each of these sets of records in turn, and subsequent chapters look at other types of record on the web. The aim of this chapter is to look at some of the general issues of using the internet for genealogical data and the major data services which provide access to these records online.

While the internet is the ideal way of making genealogical records widely available, particularly to those who are distant from the relevant repositories and major genealogical libraries, the fact is that a huge amount of work is involved in publishing such material on the web. For example, there may have been as many as 100 million births, marriages and deaths registered between 1837 and 1900; between them, the censuses of England and Wales from 1841 to 1911 include details of around 200 million individuals. Nonetheless, there has been enormous progress over the past few years in putting genealogical data online.

There are a number of ways in which genealogical data projects can be funded. Volunteer-run projects tend to rely entirely on goodwill and occasional sponsorship, while a number of projects have public funding, usually from the Heritage Lottery Fund or from academic funding sources. In such cases, access to the data is normally free.

Other record and data holders have taken four main routes to making their records available online commercially:

The first of these was the route taken by The National Archives (TNA) for its online document service (see p. 58). It is also something that is done on a smaller scale at local level, such as Essex Record Office’s Essex Ancestors service (see p. 104).

The second was the initial approach taken both by the General Register Office for Scotland (GROS) and TNA and in the first two big projects to put national record sets online: the digitization of Scottish records and the 1901 census for England and Wales. However, this monopoly approach, which was probably the only option at a time when there were no established genealogy data services in the British Isles, has not been without problems. Some of these are discussed among the ‘Issues for Online Genealogists’ in Chapter 22.

The National Archives has moved to the third type of system, which solves the issue of how to fund the initial digitization (which is very expensive) but subsequently frees up records for wider commercial exploitation. Although the 1901 census digitization started out as an exclusive arrangement between TNA and QinetiQ, the digitized images were ultimately made available for wider licensing. The result was that Ancestry launched its own 1901 census index in April 2004, with other companies following, so that the original index now has three competitors. For the 1911 census, even though the initial digitization contract involved an exclusive deal with Brightsolid/Findmypast, once the entire census had been online for six months, the images were available for other companies to license and by the time you read this, the 1911 census should be available in its entirety on three distinct different sites, with the same images but independent indexes.

The Scots have been slower to come over to this model. In spite of a public statement from GROS in 2007–08 about opening up the licensing of records, Ancestry had to go ahead with its Scottish census indexes without the agreement of GROS and unable to license the images. At the start of 2012, there are certainly more Scottish records coming online on commercial services, but still no images of those records except on ScotlandsPeople.

Record holders and data services are not the only ones involved in creating digital records — family history societies (FHSs) and individual genealogists have been creating computerized indexes for around 25 years. But generally they have neither the funding nor the technical infrastructure to mount their own commercial data service and have licensed their data to commercial services. British Origins was in fact launched in 2001 with a number of indexes which had been created by the Society of Genealogists, and in 2003 the Federation of Family History Societies launched FamilyHistoryOnline to draw on the vast body of FHS indexes. Since the closure of FamilyHistoryOnline, FHSs have been increasingly licensing their data to the commercial services, which have also been drawing on the work of individual transcribers. The obvious merits of this are that records are indexed by people knowledgeable about the records and the locality, while the technical infrastructure is high quality and resilient. However, these indexes tend not to be accompanied by images of the original records.

There are three main ways in which any historical textual source can be represented digitally:

Ideally, an online index would lead to a full transcription of the relevant document, which could then be compared to an image of the original. But for material of any size this represents a very substantial investment in time and resources, and very little of the primary genealogical data is so well served, nor is it likely to be in the foreseeable future.

The reason for this is the very great disparity between the amount of data involved in making text and images available online. In spite of advances in information technology, images require significantly more resources from the website which hosts them, both in terms of disk space for storage and the bandwidth to download them to the user. Even disregarding the labour and other costs for creating the digital images of source documents, for a large project this can mean enormous differences in financial practicability between a text-only data collection and one which includes digitized documents.

Images can be supplied economically for census records because they are central to family history and are universally needed, which means that costs can be covered. This has also been done in a number of lottery-funded projects for less widely used material, such as the Old Bailey Proceedings (see p. 124), where costs do not have to be recouped at all. It has been done for wills, where a transcription of the entire text would be commercially impracticable, but where a higher charge can be made for a complete digitized document. Generally for non-commercial projects, images of records are the exception — the only large-scale examples that spring to mind are FreeBMD (p. 70) and the new FamilySearch (p. 41), though there are quite a few smaller, local projects.

However, there are many more images than transcriptions. For a document containing running text, a transcription takes much more time to prepare than an index, and except for particularly difficult documents (e.g. a seventeenth-century will) is not really necessary, as long as there is good indexing. A project like the Old Bailey Proceedings, which has document images with an indexed transcription, is in fact exceptional. On the other hand, it is certainly true that with some sources, such as the censuses, comprehensive indexing can sometimes approach a full transcription.

Most online data, then, comes in the form of indexes linked to images, or, more often, just plain indexes. And this has important implications for how you use the internet for your research: you simply cannot do it all online. Except where you have access to scans of the original documents, all information derived from indexes or transcriptions will have to be checked against the original source. This might not be apparent to you if you are just starting out, since the first online sources you use, the GRO indexes and census records, are available as images, but you will find a very different story once you get back beyond 1837. Older printed sources will have been scanned, but there are as yet very few earlier manuscript sources which have been digitized.

The perfect index would be made by trained palaeographers, familiar with the names and places referred to and thoroughly at home with the handwriting of the period, working with original documents. Their work would be independently checked against the original, and where there was uncertainty as to the correct reading, this would be clearly indicated.

Needless to day, very little of the genealogical material on the web has been transcribed to this sort of standard. The material online has been created either in large-scale projects or by individual genealogists, and often working from microfilms, or digitized images of them, not original records. In academic projects high levels of accuracy and quality control are a fundamental part of the process, but for other large-scale projects the data are input at best by knowledgeable amateurs such as family history society members, and more often by non-specialist clerical workers. In the latter case, there will always be a question about the quality of data entry. It is self-evident that adequate levels of accuracy can only be achieved where there are good palaeographical skills, and knowledge of local place-names and surnames.

Even so, one must recognize that our manuscript historical records are sometimes very hard to read, never mind transcribe with absolute certainty. Although I am quite critical of the quality of some of the online indexes, one cannot escape the fact some of the errors are completely understandable, and one cannot really expect a commercial index to a census of, say, 20 million individuals to allow transcribers five minutes to stare at every difficult surname. When compiling some census error statistics for Census: The Expert Guide (see p. 36), I spent many hours poring over the pages for a single small enumeration district and was still left with an average of perhaps one surname every other page I could not be absolutely sure of. It would be unfair to expect non-expert clerks working to commercial targets to do better. To see the sort of thing a transcriber has to cope with, look at the scans for a servant in the household of Sarah Maskell in the 1871 census for Peckham (RG 10/734, fol. 64, p. 54) shown in Figure 4-1. At the top is the greyscale image from Ancestry, below it the black and white scan from Origins. The latter seems slightly easier to read, but I would be surprised at anyone claiming to identify the surname with 100 per cent confidence from either of them.

Figure 4-1: Could you transcribe this name with confidence?

The only area where one can expect a lower error rate is in the transcription of printed sources such as trade directories, where problems of identifying names or individual letters are less great. On the other hand, printed sources lend themselves to optical character recognition (OCR), but this is a mixed blessing. Although OCR is much less labour-intensive than manual transcription, it can produce spectacularly inaccurate results where the original documents are poorly printed, and therefore requires laborious proof-reading to guarantee accuracy, something that is simply not practicable in a large project. You can get a good idea of the limits of OCR from the recently launched British Newspaper Archive, discussed on p. 198. Figure 4-2 shows two identical reports on the loss of a naval ship, one almost perfectly captured, the other quite seriously garbled.

Figure 4-2: Optical Character Recognition — the British Newspaper Archive

Nonetheless, in manually created indexes there are some types of error which really are easily avoidable: those which are the result of poor data validation. Validation is an essential component of any data-entry project — it means checking that everything entered is, if not demonstrably correct, at least plausible. Of course, it’s one thing to do this with, say, a modern postcode, where it’s a simple matter to check that it is present in a list of valid postcodes or that it at least has the correct structure for a postcode. It is much harder to do the same with handwritten historical sources, particularly where surnames are involved. Even so, there have been some notable and entirely avoidable failures in major genealogical projects, which have reduced their reliability and usefulness.

Perhaps the most notorious of these was in the original release of the 1901 census, which had individuals with biologically implausible ages over 200. You’d have thought those entering the data might have had second thoughts about these themselves, but even so, given that data-entry errors are inevitable, why was there no mechanism in place to spot data which cannot possibly be correct?

In other cases, there are things that might be right, but are statistically so anomalous that they need individual checking. For example, all the census indexes have significant numbers of people indexed with a gender which does not seem to match with their forename. It’s easy to get a name wrong in a census transcription, whether by misreading or miskeying, and sometimes the error will be down to the census enumerator. But some of the errors will be self-evident, because of gender differences in naming — it is a trivial matter to query a database for gender errors with common forenames, to flag entries that need checking.

Sometimes a lookup will suffice to trap errors: there are some strange misspellings of place-names in the census indexes (e.g. Harimersmith for Hammersmith), or some strange combinations (Somerset, London?). Ancestry has the Sarah Maskell, whose servant was Helena from Figure 4-1, born in Syrian Arab Republic, Hange Common, instead of the admittedly hard-to-read Surrey, Ham Common on the original. But one doesn’t need to see the originals to know that these transcriptions simply must be wrong. Couldn’t they have been checked against a gazetteer? Even if it was not possible to fix them immediately, could they not have been flagged as doubtful, for later investigation?

Even with forenames, one ought to be pretty suspicious of a name that is not in the forename dictionary. I suppose it’s possible that England in 1891 had bearers of the forenames Gluyabeth or Iomnic, as two of the indexes would have it, but even without seeing the originals in Figure 4-3, I bet you could guess that the first ought to be Elizabeth and the second either Dominic or Jonnie (actually the latter). It’s an obvious enough principle: even if a name is hard to make out, it’s much more likely to be a badly written common name than a badly written name with no other recorded instances. From a purely pragmatic point of view, the descendants of Gluyabeth would probably guess at Elizabeth as a plausible transcriber’s error, but hardly vice versa. There are certainly problems with the ways these names are written in the original (both seem to have too many strokes), but you would have to be absolutely sure there was no alternative other than Gluyabeth to put that down as your transcription.

Figure 4-3: Two entries from the 1891 census for Islington

But given that there will always be genuinely hard-to-read entries, the question is how they are treated. Techniques for editing manuscript documents to indicate uncertainties of reading were available long before the advent of computers and much work has been done by those who edit historical manuscripts on ways of indicating variants and unreadable text in electronic editions (see the Text Encoding Initiative at <www.tei-c.org>). So could genealogical projects not take account of this? As far as I can see, the major transcriptions used by genealogists rarely use any mechanism (and certainly nothing more sophisticated than a question mark) for indicating that an individual character or a word is not unambiguously decipherable, in spite of the fact that it is a common enough experience for every genealogist. The transcriber simply puts their best guess, a solution which is utterly inadequate and entirely unhelpful to the user. For example, the barely legible surname in Figure 4-1 is transcribed by Ancestry as Boucha and by Origins as Bnecker. Neither is obviously right, and both seem reasonable attempts in the circumstances. But surely neither of the transcribers in this instance can have been confident that their reading was correct. It would be much more helpful for a data provider to admit that there cannot be a definitive reading here and recognize that someone looking for Bnecker or Boucha, or a range of similar names, should be shown this entry as a possible match.

Why don’t the electronic transcriptions do this? Because, to be fair, it’s actually quite difficult to do. Having complicated ways of indicating doubtful characters is all very well, but it has two unwelcome repercussions. For a start you would have to teach your transcribers how to use them and check that they were doing so correctly and consistently. Then you would have to modify your search engine to retrieve these entries when something close enough was entered. The real solution then, is to have good techniques for identifying loose matches, and all the data services give you the option of choosing a less exact match, in ways which are discussed later in this chapter (p. 39).

But all this points to another issue which underlies much of the difficulty of finding people in online genealogical databases — they do not distinguish clearly between a transcription and an index. The job of a transcriber is to reproduce exactly the letters that can be identified on the original page, that of the indexer to make things findable. The problem with Gluyabeth only arises in a transcription. With a proper index the answer is simple: you link this entry to both Elizabeth and Gluyabeth. An index is a finding aid, and it is much better for it to give occasional false positives than for it to regularly ignore obvious, not to mention more likely, alternative readings.

This question also arises very noticeably in the representation of place-names, and Guildford in Surrey is a good example. There are two obvious alternative spellings one might expect to find: Guilford and Gilford, and both do in fact occur in records. The question is: how should these be treated? The transcription approach is the simplest — just record what is written. But the problem with this is that the user has to try all the alternatives. The index approach is more complex: either the spelling can be normalised or there can be multiple index entries. Either way, in a search for someone born in Guildford, Surrey, you should also find those whose birthplaces are recorded as Guilford, Surrey or Gilford, Surrey. Normalisation can be risky, though: there is actually a Guilford (in Pembrokeshire) and a Gilford (in County Down). Also, it does something that indexers and transcribers are rightly keen to avoid: interpreting the records. That’s the genealogist’s job! But while it is not legitimate to transcribe Guilford as Guildford, there can be no harm in indexing a single record under both Guilford and Guildford.

But if normalizing can be problematic, multiple index entries can be hard work — how far should one expect indexers to go to list alternative spellings? In fact, it depends: in the case of county names, it really shouldn’t be a challenge. There are only 53 historic counties in England and Wales. We know what they are, we know their recognized alternative names (Shropshire and Salop, for example), and likely spelling variants are easily guessed (Surrey and Surry). There is no reason why county names should not be normalized or the variants correctly matched: the user shouldn’t have to guess whether a census enumerator happened to use Devon or Devonshire. In fact some sites go further: they don’t even run the risk that users might get the county spelling wrong, but offer a drop-down list for you to select from. Perhaps the real problem is not that the various sites take different and legitimate approaches, but that it is not always obvious which approach they take.

So how good should we expect the online indexes to be? When the GRO placed the tender for the DOVE project (p. 68) it specified a maximum error rate of 0.5 per cent. This sounds quite small, but in a large project it would mean a lot of records with errors. If this error rate requires that 99.5 per cent of records should be completely correct, that would still mean one million civil registration records with an error in one field or another. More likely, it means 99.5 per cent of fields should be error-free, which would result in around one million wrong surnames, another million wrong forenames, etc. You may think, therefore, that 99.5 per cent sets the bar too low, but for the censuses at least, where some comparative statistics have been compiled, none of the commercially available indexes gets anywhere near this figure.

For Census: The Expert Guide I analysed the indexing errors for two sample enumeration books, across three major data services, the work, therefore, of six individual transcribers. In each case, I checked the accuracy of three fields (forenames, surnames and birthplaces), giving a total of 18 different error-rate figures. The individual figures (online at <www.spub.co.uk/census/tables>) are not really of any importance: they’re several years old and based on a tiny and not remotely representative sample. But they show clearly that our expectations of accuracy should not be set too high. Only four of these error rates fell below 3 per cent, while in seven cases the error rate was over 10 per cent. That means at least one wrong forename, one wrong surname and one wrong birthplace per census enumeration page.

Since I excluded all the cases where the original was so illegible that there could be no single correct version, these were all errors that were in principle avoidable. There seemed to be four main sources of error:

These figures suggest that for the GRO’s digitizers to hit their target of a 0.5 per cent error rate would be a genuine cause for congratulation. But it is also important to note the census error rates cannot necessarily be applied to all online data. There is a whole category of material which ought to be much more accurate: records transcribed by individual genealogists or family history organizations. These are not produced under commercial time pressures and those involved tend to be experienced indexers who are very much more familiar with the nature of the records and highly motivated to produce accurate work. And, of course, the number of records will be a fraction of the 20 million or so in a census, which makes quality control much easier.

On the whole, my view is that there are relatively simple error checking and quality control measures which could be implemented with only a bit more trouble. Genuine indexes rather than searchable transcriptions would solve many problems about uncertain readings, but might bring additional complications. And of course, we have to accept that there will always be an irreducible core of illegible words — there are many cases where the ink on an original document is too faint to give any certain letters at all — and we simply have to live with these and find ways around them.

On a more positive note, though, it is worth remembering that although all indexes are subject to error, the great virtue of online indexes is that mistakes can be corrected. In printed or CD-ROM publications this sort of error removal can only be undertaken if and when a subsequent edition is produced, but the systematic errors in the 1901 census were dealt with reasonably promptly. All the data services have a mechanism for users to submit details of errors and suggest corrections, though how (and how promptly) these are dealt with varies between services. Ancestry, for example, does not modify the original transcription, but allows users to add ‘updates’ (there is a ‘View/Add Alternate Info’ link on the page for each record). These are not checked but are included in search results and indicated as such. Findmypast, on the other hand, checks submissions (made from the ‘report transcription error’ link in the image viewer) and modifies the data if the correction is accepted.

Also, one must be pragmatic: as long as an error does not prevent you actually locating an individual, then checking against the digitized image or the original record will provide the correct information. That means errors in gender or occupation may not be very significant — as long as you don’t specify these in a search, that is. On the other hand, large errors in ages and misspellings of surnames and birthplaces may well make someone effectively unfindable. Even with fuzzy name-matching facilities, you may need to be imaginative in your searching if your initial search fails. Also, as with any transcription or index, a failure to locate an individual in an online index does not permit you to draw negative inferences.

The great advantage of the censuses in particular is that there are several independent indexes available on a pay-per-view basis, so if you cannot find an individual on your preferred subscription service, there is a low-cost alternative. Unfortunately, this is not the case for most other datasets.

Even if the online indexes and transcriptions were perfect, there would still be potential problems in locating an individual in a set of digital records. For a start, many of the records themselves are incomplete and flawed in various ways. The gaps in census records are generally well documented, but those for parish registers and many older records are often hard to pin down. Also, you start every search with a certain amount of prior information, but it’s quite possible for that information to be inaccurate or at least incomplete. Sometimes our ancestors lied or were forgetful when giving information to officials; in other cases perhaps the evidence or over-reliance on the memory of an ageing family member has led you to make an assumption that turns out to be wrong. These two problems are in fact less of an issue when working with original records — you will almost always notice an entry in, say, a parish register that is similar to but not exactly what you expected. In an electronic index, though, too precise a formulation of your search may have the effect of making that entry invisible.

Techniques for getting the best results when searching census indexes, which are generally the most complex online records, are discussed in detail in Chapter 5 of Census: The Expert Guide, but it is easy enough to summarize the main techniques for more satisfactory searching:

This last point arises from one of the fundamental problems of searching online indexes to genealogical records: names have in the past been subject to much more variation than we are now used to. Add to that the contemporary idiosyncrasies when a name was written down and the possibility of modern mistranscription, and it is clear that searching for individuals in historical records can be far from straightforward.

There is no definitive online (or indeed offline) source to help you to decide whether surname X is in fact a variant of surname Y, or what variant spellings you can expect for a particular name. However, if a name has been registered with the Guild of One-Name Studies the Guild’s online register at <www.one-name.org/register.shtml> may give some indication of major variants, and it will be worth contacting the person who has registered it. Posting a query about variants on one of the many surname mailing lists and query boards (see Chapter 18) would also be a sensible step.

The search forms for online records almost always have some mechanism for choosing either an exact or a looser (‘fuzzy’) match with what you type in the search box. In some cases, that’s all they do, without any indication how matches are made; in other cases a site will use an explicit method for deciding which variants to include. FamilySearch and Ancestry take the former approach and their default is a fuzzy match — there is a check-box for you to tick if you instead want an exact match. Otherwise, the main possibilities are the following:

| Wildcards: | Many systems allow you to use a ‘wildcard’, generally an asterisk, to stand for any number of letters (including none), so Brook* would find Brook, Brooke, Brooks, Brookes, Brooker, Brookbank, Brookshaw, etc. Those with Scots ancestors will find this useful to search simultaneously for ‘Mac’ and ‘Mc’ names with M*c. On some sites you can also use a question mark to stand for a single character. In general, though, you cannot use a wildcard at the beginning of a name. |

Soundex: |

A venerable system with considerable limitations, which assigns a four-character code to each surname and regards two surnames as matching if they have the same code. Details of Soundex can be found at <www.archives.gov/research/census/soundex.html> and some of its shortcomings are described in my article ‘Soundex — can it be improved?’ at <www.spub.co.uk/cig/605christian.pdf>. ScotlandsPeople is the only major UK site to use it. |

NameX: |

A more modern, proprietary system works by taking the name you are starting with and giving every other name a score based on how closely it matches. This allows you, in principle, to look at only close matches or to include more distant ones. Image Partners, who developed NameX, have a demo on their site at <www.namethesaurus.com/Thesaurus>. |

One general problem, though, is not solved by any of these methods: florid initial letters are easy to mistranscribe and this will often lead to name forms that cannot in any way be regarded as ‘variants’.

The Thesaurus of British Surnames is a project to develop an online thesaurus of British surname variants. The ToBS website at <www.tobs.org.uk> does not have details of individual variants but has a number of resources relating to the issues of surname matching, including papers on the problems of identifying surname variants, and a comprehensive bibliography on the subject. Origins has a good discussion of the problems of identifying surname variants in historical records in its page on NameX at <www.originsnetwork.com/namex/aboutnamex.html>.

In January 2012, Ancestry, WeRelate and Behind The Name announced a joint project to provide for improved surname matching in the form of an open-source database of name variants. The database can be searched at <www.werelate.org/wiki/Special:Names> and you can add variants to the search results for any name. There does not seem to be any quality control on new submissions. There is more information about the project at <www.werelate.org/wiki/WeRelate:Variant_names_project>.

A particular issue for those with Irish ancestors is that many modern surnames are anglicized forms of Irish-language surnames. Indeed it may be impossible to trace an Irish ancestor in the Irish censuses (see p. 95) without knowing the original Irish form, not something which can normally be guessed at by a non-Irish speaker. The best resources on Irish surnames are found on Library Ireland at <www.libraryireland.com/Names.php>. This has seven, mainly nineteenth-century, works on Irish names. ‘Some Anglicised Surnames in Ireland’ gives the Irish form for each anglicized name, while ‘Irish Names and Surnames’ gives the anglicized forms for Irish originals. Wikipedia’s <Irish name> article has a list of about 200 names, with variants and anglicized forms.

While most of the large sites offering a range of genealogical records are commercial, one of the most significant is entirely free: the LDS Church’s FamilySearch site at <www.familysearch.org>. The site first went live way back in 1999 with the International Genealogical Index (IGI). This is a worldwide collection of church records, mainly baptisms, including millions of entries for the British Isles. This was followed in 2003 by the 1881 Census Index for England and Wales.

In 2006 FamilySearch launched a project called FamilySearch Indexing, in which all the microfilms of genealogical records in the Family History Library (see p. 221), including therefore all the parish register material in the IGI, would be indexed from scratch by volunteers for making available online. The first fruits of this came in 2008, when a pilot version of a new FamilySearch site went live for testing, and in 2011 the new site replaced the old at <www.familysearch.org> (Figure 4-4).

Figure 4-4: FamilySearch home page

The old site remains accessible at <www.familysearch.org/eng> even though most of the data seems to be available on the new site. Needless to say, this is by far the most ambitious genealogical indexing project ever attempted and no doubt will take many years to complete. So far over 500 million records have been indexed.

On the new site the genealogical records are in the ‘Historical Records Collection’ and cover a wider range than just church and census records — among the material already on the site are school, workhouse and probate records.

The majority of the collections on the site form well-defined record sets from a particular source, which for the UK is usually from an individual county (e.g. Cheshire Bishop’s Transcripts or West Glamorgan Electoral registers). But a few of the datasets are actually the material from the International Genealogical Index (IGI) and related sources, divided into national collections for England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland. However, an important change has been made to this material: it originally included not only the results of official transcription efforts but also unverified (and in practice often inaccurate) submissions from individual church members. These now all seem to have been removed, making the quality of the data much higher. This does not mean it’s wholly reliable, though — just while trying some test searches, I came across a load of entries for Leominster, Sussex (it’s in Herefordshire!) and Pervensey, Sussex (for ‘Pevensey’).

If you are new to the site, it is useful to get an overview of what’s available by using the ‘Browse by location’ options lower down the page. This will give you a list of all the countries in each region, from which you can select the one you want. All English records are under ‘United Kingdom’ though Wales, Scotland, Ireland, the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man have separate entries. For all but the UK there are so far only a handful of collections. (See Figure 4-5.)

Figure 4-5: FamilySearch: UK Historical Record Collections, Birth, Marriage and Death collections

For the newly indexed collections, there is wide variation in what each offers, based on how far the work on a particular project has progressed and the terms of any agreement with the original repository, but there are three basic patterns: an index alone, an index with a link to an image of the original record, and an unindexed series of document images. In the longer term all the images will eventually be accompanied by indexes, but the reverse may not be the case — where FamilySearch does not own the rights to a set of images, it may be unable to make them publicly available. In the case of some of the censuses, the indexes have been supplied by commercial partners and links for the images take you to the relevant commercial site, where registration and payment will be required. (This limitation does not apply if you are accessing the site from a Family History Center.)

Although you can search records just by entering forename and surname on the FamilySearch home page (Figure 4-4), this will search all 850 or so data collections on the site from over 60 different countries. Since this includes 320 million entries from UK and US censuses, any English or Celtic surname will inevitably be very frequent. Even so, this can be useful: it can be a way to trace people who you suspect might have migrated; and for a one-name study it is a quick method of establishing which countries a surname is found in. But unless an ancestor has a reasonably unusual name, it is better to narrow down the search by using the ‘Search by Life Events’ or ‘Search by Relationships’ filters. The first of these allows you to enter a place, though if you’re searching all the data this is less useful than you might think: if you enter, say ‘Wales’ in the ‘Place’ field, you will not only get some Welsh parish register entries, but any UK or North American census where Wales is the place of residence or place of birth. Unfortunately, there is no way to search only the British Isles records, or just those for, say, Scotland. But if you know where you ancestors came from, you are in any case much better off searching the collections for the individual nations of the British Isles and narrowing down with a county.

There is one important caveat about the dates given for these collections: when it says, for example, ‘Parish registers 1538–2000’, that does not mean that this is the coverage for every parish in the area, just the date of the earliest and most recent records. For a start, many parishes do not have records going back as early as 1538, and in some smaller parishes the church will still be currently using a register which was begun decades ago and has therefore not yet become available for filming. In addition, the site is a work in progress: these dates apply to the whole of the material in the collection, but the work is being done in phases and indexing is not necessarily complete. However, the wiki page for the collection (follow the ‘Learn more’ link on the search page or any search results page) may give more detail of the dates so far under the heading ‘Collection Time Period’. Where a collection is just available as images, there is no problem seeing the exact coverage because the way the material is organized will reveal what is included. Unfortunately, the wiki page for each collection does not list exactly which parishes have so far been covered for which dates, but the FamilySearch Indexing Updates page on the wiki at <www.familysearch.org/learn/wiki/en/FamilySearch_Indexing_Updates> gives latest details of the percentage of each collection completed. A very rough idea of the dates covered for a particular place can be gained by doing a search on place-name only, as discussed on p. 101. This will certainly show the earliest and latest records, though gaps in the coverage may not be readily apparent.

The FamilySearch Indexing collections are missing one very useful feature: once you have a set of search results there is no easy way to download the information, whether for an individual record or for a whole set of search results, something which would be particularly useful if you have many ancestors in a parish or county and, of course, for one-name studies. This was always possible on the older site and given that its absence must be a source of irritation to most long-term users, one must hope the feature has just not yet been implemented.

FamilySearch is not just a home to the Historical Records Collection and it contains much other material, notably the wiki and the online lectures and courses discussed in Chapter 2, and the pedigrees submitted by individual genealogists, which are discussed in Chapter 14.

Among the other material that is particularly worth looking at:

The individual categories of record on the site are discussed in the relevant later chapters, and, since church records are still the main thing that users want to search, a more detailed look at how to use the historical record collections is provided in Chapter 7.

The following chapters cover the various types of record and look at sites relevant for each. But there are a number of major commercial sites which have datasets drawn from a variety of different records, and these are discussed here for convenience. All the sites mentioned are constantly adding to their data, sometimes on a monthly basis, so you will almost certainly find there is a wider range of data than mentioned here. Prices, on the other hand, have tended to be very stable, and are not likely to be much higher than those quoted.

The sites described here are all mature services and most offer facilities beyond their data collections which space does not permit coverage of here. In particular, they offer community facilities like discussion forums and shareable family trees. It should be easy to discover what additional features the sites offer, and they can sometimes be used without payment, though you will undoubtedly need to complete some form of registration.

The details given below are based on what is available on the sites in March 2012 but I have included mention of some datasets which I have not seen but which are already in preparation and should be released in the following months.

There are major data collections such as FreeBMD (see p. 70) and FamilySearch (see above) which do not charge for access to their material, and there are smaller free collections which are maintained by volunteer efforts or have some source of public funding. But generally there is a charge for access to larger collections of digital records. There are three basic methods that sites use to levy their charges: subscription, pay-per-view and online shop.

Initially sites tended to be pay-per-view, and Ancestry UK was the sole data service which was launched with a subscription-only system. This was almost certainly because these services tended to start with just a small number of datasets — Findmypast, for example, initially had only the BMD indexes. Also, I suspect they were unsure whether the UK’s notoriously stingy genealogists would be prepared to commit themselves to an annual charge. But for heavier users a subscription is much more economical, and as the sites have added more and more data, this option has become more attractive both for the companies and for the users.

Now things are much more mixed. Of the major data services discussed later in this chapter, only ScotlandsPeople and two sites specifically targeted at the less experienced and perhaps less committed family historian, Genes Reunited and RootsUK, are exclusively pay-per-view. One of the reasons for this shift is that the data services have started offering things like scanned trade directories where it makes no sense to charge users for each page viewed. Origins went over completely to subscription some years ago, though it is planning to re-introduce a pay-per-view option in 2012, while Ancestry, as a requirement of its census licences from The National Archives, has introduced a pay-per-view option.

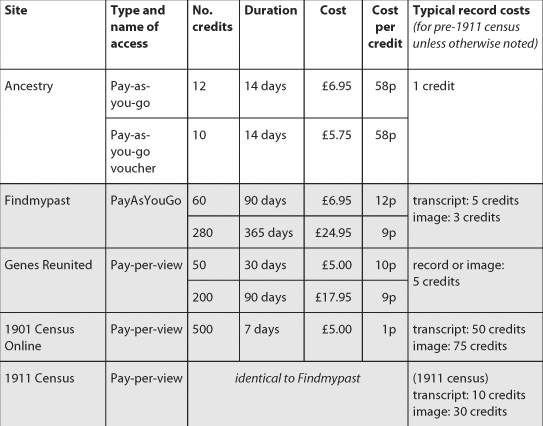

In pay-per-view systems you pay, in principle, for each item of data viewed. However, it is problematic to collect small amounts of money via credit and debit cards, not to mention tedious for users to complete a new financial transaction for each individual record they want to view. Therefore, all such systems require you to purchase a block of ‘units’ or ‘credits’ in advance, which are then used up as you view data. Generally units are available only in discrete amounts, and work with either real or virtual vouchers for round sums of money. There is usually a time limit, which means you could have units unused at the end of your session. You won’t be able to claim a refund, but in some cases you can carry forward unused portions of a payment to a subsequent session.

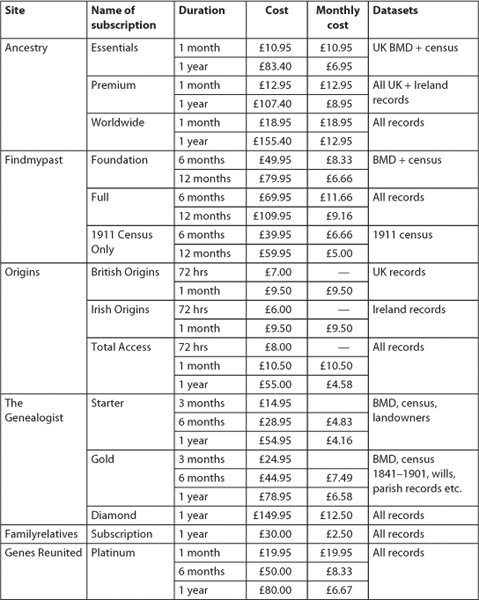

Table 4-1: Commercial data services in the UK: subscription prices and facilities (March 2012)

In an online shop, whether it’s for genealogical data or for physical products, you add items to a virtual ‘shopping basket’ until you have everything you want, and pay for all of them in a single transaction at a virtual ‘checkout’. Only then can you download the data you have paid for. Such a procedure would make little sense for individual data entries, but is a good way of delivering entire electronic documents, so it is ideal for the wills available from The National Archives or ScotlandsPeople (see Chapter 8). It also allows items to be priced individually, though these two services in fact charge at a flat rate.

An overview of the current charging systems for the major commercial data services in the UK is shown in Table 4-1.

A useful table comparing the data and facilities offered by the four main data services was published by Who Do You Think You Are? Magazine and is available at <www.thegenealogist.co.uk/images/index/wdytya_j12_comparisonchart.jpg>

Table 4-2: Commercial data services in the UK: pay-per-view prices (March 2012)

In July 2014 Origins was sold to Findmypast, which acquired all its data. All Origins sites closed down.

Origins at <www.origins.net> was the first UK genealogy data service, and its website comprises three distinct services: British Origins, Irish Origins, and Scots Origins.

British Origins at <www.britishorigins.com> went live at the start of 2001 (under the name English Origins) and currently includes the following main categories of material:

During 2012 the site will be adding monumental inscriptions and poor law records, and continuing to expand the scope of the National Wills Index.

The records on British Origins will mostly be of use to those who have already got some way with their pedigree, as many of the datasets only go up to the mid-nineteenth century. Unlike most other data services, Origins does not have civil registration records and is not aiming at a complete collection of censuses. The range of records for London, Middlesex and Surrey makes this site especially valuable to those with ancestors from the City and the modern Greater London area.

Irish Origins at <www.irishorigins.com> offers a wide range of Irish datasets, of which the most significant are Griffith’s Valuation (1847–1864) and other census substitutes, a substantial collection of wills from the thirteenth to the nineteenth century, and electoral registers from the 1830s. There are also militia records, passenger lists, and nineteenth century trade directories.

Among the further datasets planned are the records of the Royal Ulster Constabulary from The National Archives and a collection of around 200 directories covering the period 1751 to 1900.

At the time of writing Scots Origins offers free searches of christenings and marriages from the IGI (see p. 100) and a place-name search for the 1881 census. But Origins plans to develop this into another subscription service with indexes to all the Scottish censuses and a number of other Scottish datasets, with the first material being released sometime in 2012.

Origins was originally a pay-per-view service but it moved to a subscription system in July 2004. There are a variety of subscriptions: 72 hours or one month for British or Irish Origins, with an additional annual option for the ‘Total Access’ subscription. The prices are given at <www.originsnetwork.com/signup-info.aspx>. If you just want to try the site, the 72-hour subscriptions are relatively expensive, and the one-month option is only a third more for much longer access. Origins have announced, however, that they will be re-introducing a pay-per-view option during 2012. At the time of writing, no payment details were available for Scots Origins, nor how this will integrate with other subscriptions.

There are, broadly speaking, three different types of result you may get from a search on Origins. In the case of many of the indexes, you will probably get all the available information. For other records, Origins has a scan of the original document, which you will be able to view. Finally, for some of the records, the index provides a document reference and you can place an online order for a copy of the document to be made and posted to you (or, of course, you can simply visit the relevant repository). There is a separate charge for these copies as they are made by the supplying organization, not Origins itself.

While the number of search fields is more limited than some other services, they will certainly be enough for most purposes. The site uses the NameX surname-matching system (see p. 40), which has the useful feature that you can select how close a match needs to be. The site’s indexes have a good reputation for accuracy.

The Scottish civil registration indexes were the first genealogical records in the UK to be put online by a government agency, when Scots Origins opened its electronic doors in 1998 to provide the data on behalf of GROS. In 2002, the contract for the online service was awarded to Scotland Online, who now provide it on the ScotlandsPeople site at <www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk>. In 2008 Scotland Online took over Findmypast (see below) and changed its name to Brightsolid.

The site was initially designed just to supply the civil registration, census and parish records, but has now expanded its brief to cover all national records, including those previously on the National Archives of Scotland’s Scottish Documents site at <www.scottishdocuments.com>, which no longer carries records itself.

ScotlandsPeople offers the following Scottish records:

Almost all of this data is exclusive to the site, though Ancestry and Findmypast have their own indexes to some of the Scottish censuses, but without images.

This is a pay-per-view system and you purchase access in blocks of 30 credits for £7. An initial search is free of charge, but this only tells you how many hits your search produces. Each page of search results costs you one unit and includes a maximum of 25 entries, while viewing an image costs five units. In addition to viewing the scanned registers online, you can order a copy of the relevant certificate for £10. This is paid for separately and does not come out of your prepaid units. The absence of a subscription option is an issue for heavy users of the site, especially since you have to pay for each page of search results, which discourages more speculative searching.

The wills and coats of arms are not part of the pay-per-view system but are sold via an online shop (see p. 118).

The site keeps a record of all search results and certificates that you have paid to view, and these can be retrieved at any time, not just during the session in which they were first accessed. You therefore don’t need to pay to return to the site to review material you have already paid for, even if you have run out of valid units. You can also download the list of all the records you have viewed in a number of formats

Unfortunately the quality of some of the images is rather poor by the standards of the other data services discussed here: most of the records are black and white, rather than greyscale like photographs (see Figure 5-6). This makes for difficulties in reading some of the poorer quality originals, particularly as they are scanned at only 200 dots per inch. More recently added records, including the 1911 census and the Catholic records, are much more satisfactory: they are in colour and at higher resolution, and can be downloaded in JPEG format. The fact that you have a range of different viewers to choose from is also very welcome.

The Ancestry.com website <www.ancestry.com> is the largest commercial collection of genealogical data. It holds over 25,000 separate datasets, many of them derived from printed materials which may be more or less difficult to find outside a major genealogical library. Ancestry is a long-established US company, and started to host UK data in 2002 with the launch of Ancestry UK at <www.ancestry.co.uk>, offering a subscription covering the UK data only. At the start of 2012, the UK data amounts to around 1,000 datasets.

Among the main records for the British Isles are:

The list of datasets available on Ancestry UK is in the ‘Card Catalog’ at <www.ancestry.co.uk/search/collections/catalog/>: use the filter options in the left-hand column to see what is available for a particular country or type of record.

Ancestry has traditionally been a subscription service, and a quarterly or annual payment provides unlimited access to all databases included in the particular subscription package. There are three levels of subscription:

With the introduction of the UK censuses in partnership with The National Archives, a pay-per-view option was introduced, with a payment of £6.95 permitting 12 page views within a 14-day period. This system covers not just the census, but all datasets on the site. If you use the pay-per-view option, you can extend it to a quarterly or annual subscription by paying the difference.

Ancestry offers a 14-day free trial offer, but if you sign up for this you should be aware that a full subscription will be charged automatically to your credit card if you do not cancel before the end of the trial period. Free access to Ancestry’s UK data is available from many public libraries, from the Society of Genealogists and from the public computer facilities at The National Archives.

For Americans with UK ancestors, there is a subscription option at the main site which includes both US and UK records. Ancestry’s Australian site at <www.ancestry.com.au> includes UK records in all subscriptions.

Although Ancestry is a commercial service, some of the material is free of charge. For example, FreeBMD’s GRO index data is available here as well as on FreeBMD’s own website (see p. 70). Some of the non-record facilities on the site are also available without subscribing.

The site has extremely flexible search facilities, and a striking feature is that searching does not require a surname. This can be very useful if looking for a woman under an earlier or later married name, or if you have simply failed to find the right person searching on the expected surname. While you can choose exact or loose search, with the latter, the site orders results by its own ranking system, which is far from transparent. Ancestry’s image quality is generally good and its image viewer has a range of useful options. The site has suffered from some notable lapses in data validation in its census indexes (see p. 33), but the flexibility of the search does help to compensate for errors.

A useful blog is the Ancestry Insider at <ancestryinsider.blogspot.com>, which offers an ‘unofficial, unauthorized view’ of Ancestry.

Findmypast at <www.findmypast.co.uk> went live in April 2003, under the name 1837online, offering the GRO indexes. Since then, the company has expanded its material considerably, and in 2008 it was taken over by Brightsolid (see above) and became involved in the project to digitize the 1911 census. At the end of 2009, the Office of Fair Trading approved Brightsolid’s acquisition of Friends Reunited, which meant that it took over Genes Reunited. The site offers:

The Scottish census indexes are to be completed during 2012, and partnership with the British Library will see the addition of newspapers (see p. 198), electoral registers, and India Office records.

The site operates both subscription and a pay-per-view (they call it ‘PayAsYouGo’) systems, and the prices are given at <www.findmypast.co.uk/payment-step1.action>. The three different subscription options give access to different datasets: the 1911 Census only subscription, as you’d expect, gives access to only this dataset; the Foundation subscription covers all census and civil registration records; the Full subscription covers all records. The only real benefit of the 1911 only subscription is for those who do subscribe to another data service which does not yet have the full 1911 census. There is a 14-day free trial of the Foundation subscription data.

Findmypast also operates the distinct 1911 census site at <www.1911census.co.uk> (see p. 90) and pay-per-view units purchased on either site are available at the other. In May 2011, Findmypast launched a dedicated site for Irish records at <findmypast.ie> in association with Eneclann, an Irish company with a genealogy research and data publishing background. Prices are at <www.findmypast.ie/payments/subscription>. The site is still very new and the initial records include:

Material to be added during 2012 includes 13 million cases from Petty Sessions Court Registers and civil registration records.

The company has an Australian site at <www.findmypast.com.au>, a US site at <findmypast.com>, and also runs a dedicated pay-per-view site with passenger lists only, Ancestorsonboard, at <www.ancestorsonboard.com>.

The range of search facilities is very comprehensive for all the datasets, with both basic and advanced searches for the census records as well as the ability to search on a census reference.

With its pedigree database and contact service, Genes Reunited at <www.genesreunited.co.uk> is best known as a social networking site, and this aspect of the site is covered in Chapter 14 (p. 233). In 2006, it added the 1901 Census index followed by further data collections, licensed from The Genealogist. Brightsolid’s acquisition of Friends Reunited in 2010 meant that it took over Genes Reunited. The data collections are few in number compared to the sites discussed above:

These indexes and images are identical to their equivalents on Findmypast with the exception of the 1901 census — Genes Reunited still offers the original 1901 census index and not the separate index created by Findmypast.

The site’s pricing appears complicated since it combines subscription and pay-per-view options. First, all data is available on a pay-per-view basis. Second, there is a Platinum subscription which covers the same material as Findmypast’s Foundation subscription, with unlimited access to all civil registration and census records (as well as the contact service), though you need to use pay-per-view for other records. The Standard subscription does not cover records at all — it only covers the contact service. However, the site offers images of the original GRO index books free to all users, though the individual names are not indexed.

In spite of the duplication between Genes Reunited and Findmypast, the two sites are really aimed at different types of user. Genes Reunited, with subscriptions for only the core genealogical records and very basic search facilities, is clearly designed for the relative beginner, mainly perhaps the person who has uploaded a family tree for their immediate family and wants to start looking at nineteenth-century records. Certainly, once you need to move beyond civil registration and census records, Findmypast’s Full subscription is the better value for money, and its more flexible search options are ideal for the more experienced family historian.

The Genealogist at <www.thegenealogist.co.uk> is a data service run by S&N Genealogy Supplies, well known as a software retailer and publisher of genealogical records on CD-ROM. It provides a wide range of resources, including:

Additional records in the pipeline include major newspapers and an expanded range of Welsh parish registers.

There are a range of payment options:

Full details are available from <www.thegenealogist.co.uk/nameindex/products.php> and the choice of datasets is shown at <www.thegenealogist.co.uk/compare.php>.

The civil registration records are also made available on The Genealogist’s BMDindex site at <www.bmdindex.co.uk>, which operates a pay-per-view system. They also run a separate site BMDregisters at <www.bmdregisters.co.uk>, which contains non-conformist and non-parochial birth and burial records, described on p. 109.

The Master Search offers not only a person search but also, for the census records, family and address searches. A particularly interesting option is the facility to search for family members solely on the basis of their forenames, which is a novel way to get round seriously illegible surnames in census records. Apart from the Master Search, there are also separate, tailored search facilities for the individual categories of record.

The Genealogist also runs RootsUK at <www.rootsuk.com>. This site is targeted more at the relative newcomer and offers only the data that those starting their family history will need, along with much simpler search facilities. This makes the site ideal for the relative novice but probably too limited for the experienced genealogist. The data available comprises:

All indexes and images are identical to those on The Genealogist, but the site offers only pay-per-view access, though initial searches are free. The basic search facilities are very basic (just forename and surname), but for each set of records there is a more flexible advanced search.

Familyrelatives was launched at the end of 2004 at <www.familyrelatives.com>. It started off with just the civil registration indexes, but now has a much wider range of material. The site’s datasets include:

Additions during 2012 are planned to include both Australian and US material, as well as divorce and convict records.

Familyrelatives operate both a subscription and a pay-per-view system. The latter gives access to the civil registration records and some of the military and parish records. A comparison of the two options is provided at <www.familyrelatives.com/pricing.php>.

The sites discussed above are, at the start of 2012, the most important commercial data services for UK genealogy, but they are not the only ones, and a number of local or specialized collections are mentioned in later chapters.

There are two sites specifically for Ireland (in addition to the Irish sites of Origins and Findmypast, mentioned above). The Irish Family History Foundation has a data service at <www.rootsireland.ie>, with over 188 million records, of which over three-quarters are church records. The site operates a pay-per-view system costing a rather expensive €5 per record. Searching is free, though you have to register. One significant limitation is that if you do not specify a year in your search, only the first 10 results are shown. AncestryIreland is run by the Ulster Historical Foundation at <www.ancestryireland.com>. It has birth, death and marriage records for County Antrim and County Down available on a pay-per-view basis, with free searches but, again, a rather expensive charge of £4 to view a record. There are many other types of record available to members of the Ulster Genealogical and Historical Guild, subscription to which costs £30 per annum.

The only real competitor to Ancestry in terms of worldwide coverage is the US-based World Vital Records at <www.worldvitalrecords.com>. While there is a US-only subscription, access to the UK datasets requires a World Collection Membership at $119.40. All the UK data are licensed from other companies, including military records and passenger lists from British Origins, and the England and Wales censuses from Findmypast. The site is probably not worth considering if you only have ancestors from the British Isles, but for an American family with some roots in Britain or Ireland, it could be very useful.

The data services discussed above mainly offer individual entries from much larger sets of records, but an alternative way of making records available is to offer a scan of a whole document for a one-off payment, via an online shop rather than by subscription or pay-per-view.

ScotlandsPeople in fact offers this alongside its pay-per-view service. For the Scottish wills and coats of arms, you pay a flat rate for a digital scan. In these cases, there is no transcription, just an index to help you identify the correct document. Once paid for, you can download a PDF file with scans of all the pages in the original combined in a single document.

While The National Archives does not run its own data service, and instead licenses its records to commercial partners, it does have an electronic document download facility as part of the Discovery service (see p. 210). This is not aimed solely at genealogists but at all those who need to consult its records. It therefore includes things like Cabinet papers and Ministry of Defence UFO reports. The categories of document of most interest to family historians include:

Most documents cost £3.50 to download, but medal cards are £2.

Figure 4-6: The National Archives’ Discovery service: entry for the will of Horatio Nelson

A commercial document service is The Original Record at <www.theoriginalrecord.com>, which has a very sizeable collection of indexed scans of printed records. Many of them are lists which are not available elsewhere on the web and may only be found in specialist libraries. The site does not offer a master listing, you can only find out what is available by selecting one of the decades between 1000 and 1950 to see what it contains. But, for example, the decade 1900–1909 includes:

Unfortunately, there are two things which make the site less useful than it first appears. First, the search facility permits search on surname and date range only. This is perhaps inevitable given the many different types of sources, but it makes it very difficult to be sure a match is the person you are looking for, so you may therefore end up paying for many more documents than you actually need. Second, given that uncertainty, the price per document of £4 or more seems rather high. An annual subscription, with unlimited record downloads costs £100.

One issue that faces anyone using online services that provide images of original records is the file format of the image and the viewer needed to view them. You might think that you don’t want and indeed don’t need to worry about this. But it is in fact one of the main sources of problems in the data services. Even if you can see the image without problems in your browser, are you sure that when you save it to your hard disk, you have software on your machine that can display the image? Will you be able to crop or enhance it in order to suit your own particular requirements?

It would be easy to fill 20 pages with discussion of the online services’ image facilities and how to make the most of them. Here, I will just look at the main image formats and some of the issues with the image viewers the sites use. Note that several of the data services offer alternative viewers or file formats (ScotlandsPeople offers six!), and in some cases different datasets use different image formats.

Record images on these sites are, on the whole, monochrome, since most of them have been created by digitizing microfilms made often many years ago. However, more recently filmed material, such as the 1911 census, has been created directly from the original records with digital cameras, and is in colour. Table 4-3 below shows the image formats used by the main commercial services.

Table 4-3: Image formats on the main data services

Ancestry |

Flash, JPG |

Familyrelatives |

DjVu |

Findmypast |

DjVu, Flash |

Genes Reunited |

PDF, JPG |

Origins |

TIFF |

ScotlandsPeople |

PDF, Flash, direct viewer (JPG), direct download (TIFF), Java Applet, ActiveX (Internet Explorer only) |

The Genealogist |

Adobe Acrobat is, at first sight, a pretty unproblematic format. It is not in fact an image format at all, rather a document format which can incorporate images. It is often referred to as ‘PDF’, which stands for ‘portable document format’, and Acrobat files always end in the extension .pdf. Its particular advantage for genealogical records is that it can combine many images in a single file, each on its own page. This makes it ideal for multi-page documents like a will, which can be downloaded in one file containing a separate image of each page.

To view Acrobat files you need the Adobe Acrobat Reader. Acrobat files are so widely used on the web that unless you are an internet novice using a new-ish computer, you will almost certainly have the software installed already. If not, it can be downloaded free of charge from Adobe’s home page at <www.adobe.com>. When you install it, your browser will automatically be configured so that it knows to use the reader when it comes across an Acrobat file, and it will display the document within the browser window.

Once you have downloaded a PDF file (click on the ‘Save a copy’ icon at the top left of the reader window), you can view it again by clicking on its icon — this will automatically start the Acrobat reader.

The problem with Acrobat files comes when you want to manipulate the images. You might think you won’t want to do this, but at some point you will certainly want to extract from a page just the bit you need; or you may want to adjust the contrast or brightness to see if you can read something that looks illegible. But since PDF is not a graphics format, you cannot simply load it into a graphics program to carry out these tasks. And the Acrobat Reader cannot save a file in any other format.

The way around the problem is:

At this point an image of the selected area has been saved on the Clipboard, and you should be able to paste it into your graphics editor.

JPG or JPEG is probably the most widely used graphics file format on the web. Browsers can display JPG images without additional software, and any graphics editor can be used to edit them. However, the data services do not simply display the JPG image in the browser window, but it is loaded into a special viewer page which has a range of controls at the top for things like zoom, rotate image and save.

The TIFF format is a very common image format for professional graphics work, but is not that common on the web, and browsers cannot display TIFF images without special software. ScotlandsPeople only offers TIFF as a download format, in fact. Any graphics editor, however, should be able to deal with TIFF files.

Origins recommends that you install a free viewer called AlternaTIFF, and the ‘can’t view image?’ link at the bottom of every image display page brings up information about this and how to install it. In fact, even if your browser already has a plug-in which displays TIFF images, it may be worth installing AlternaTIFF since it offers several useful tools for viewing: zooming, panning, printing and saving are all catered for. If you are using a Mac, you should find that a TIFF image is displayed automatically using Apple’s QuickTime plug-in, though this does not offer any image controls to zoom or print the page. Origins’ help page on image viewing at <www.originsnetwork.com/helpimages.aspx> covers all aspects of viewing the site’s TIFF images.

Flash is used by Ancestry and Findmypast, and is one of ScotlandsPeople’s options. It is a very widely used file format, particularly for animation, and you may well have the player software installed already. If not it can be downloaded free of charge from Adobe’s home page at <www.adobe.com>, just like the Acrobat Reader. When you save an image from the Flash player, it is saved in JPG format (see above).

DjVu (pronounced like déjà vu) is a fairly exotic graphics format and you may well never have encountered it before, which means that before you can view the images, you will need to install the DjVu viewer. Familyrelatives uses it for all images; on Findmypast it is the Enhanced Viewer and brings a number of advantages over Flash, most notably much improved download speed.

There is no need to repeat here the instructions on how to install this, which will be found on the two sites (at <www.findmypast.co.uk/helpadvice/faqs/djVu-viewer> and <www.familyrelatives.com/information/info_detail.php?id=40>). But you need to be aware that there are potential installation difficulties, depending on your browser and its configuration, so it really is a good idea to refer to the relevant help page first, and not just after you encounter a problem.

The DjVu viewer does have one significant problem: very few graphics editors can deal with images in this format, so you may be unable to edit the images with the graphics software you normally use. There are two solutions:

You don’t need to worry about this unless you want to edit a DjVu image; you will still be able to view the saved images — clicking on the file name in an Explorer window on the PC will load the image in a standalone version of the DjVu viewer.

It would be nice to make a firm recommendation as to the best of the data services discussed on the previous pages, or give them comparative scores. However, it would be very difficult to justify doing so.

For a start, it will depend on your genealogical needs and your budget. If you are on a tight budget, then you will probably want to stick to the sites with pay-per-view options rather than subscriptions. If you are already quite advanced with your family tree, you will probably want to avoid the more basic services and go for a site with a wider range of records and more sophisticated searching. All of these sites have their fans and their critics. Often people simply prefer the search facilities or the interface on one site rather than another. Many of the sites offer additional facilities, particularly the ability to maintain an online family tree, which might sway you one way or another.

The other problem is that, even if you are reading this book very soon after it comes off the press, one or more of the sites will have improved facilities and additional datasets which may increase its usefulness to you.

One thing that is certainly impossible is to say much about the quality of the data. The quality is highly dependent on the nature of the original records, and with many records indexed from microfilm rather than the original, poor quality filming can limit the quality of even the most diligently indexed records. Also, while the major sites all do significant amounts of digitization and indexing in-house, they all also license existing datasets from elsewhere, so the quality of one set of records is no guide to the quality of another. Even where direct comparisons can be made, most obviously in the census records, it would be quite impossible to take a large enough sample for a statistically meaningful result.

The three sites that suit both beginners and advanced users are Ancestry, Findmypast and The Genealogist. Origins is not really aimed at those just starting their research but is designed more for those who want to move beyond the obvious core records. If you’re a relative beginner and don’t (yet) need anything beyond civil registration and census records, then RootsUK and Genes Reunited are worth looking at. Origins and Familyrelatives probably have the best collections of Irish data, though Findmypast Ireland will no doubt be catching them up. Ancestry clearly has the largest number of datasets overall. Perhaps the only thing that can be said with certainty, for the moment at least, is that if you are researching Scottish ancestors, you will need to use ScotlandsPeople.

While in the long term, for the serious family historian, a subscription is obviously the best option overall, initially it may be worth using the free trial and cheaper pay-per-view options to get a feel for the sites which have what you want.

An issue which may definitively influence your choice may be the availability of free access. The three main commercial services all have library subscriptions available to institutions, and it may be that your local public library offers one or other of these services to ticket holders free of charge.

Other than that, there are two physical locations which offer some free access on-site:

While these may not provide everyday access if you live far from London, their locations do mean that you can combine using online data services with a research trip to consult other records.

It is not uncommon for users to experience problems with commercial genealogy sites, as indeed with all e-commerce sites. This is nothing to do with the security concerns people have about online payments (these are addressed in Chapter 18), but relate to the web browser and how it is configured. While it is not possible here to cover every eventuality, most of these problems arise from a readily identifiable set of facilities used by commercial websites, and are more or less straightforward to solve. Sites that use such facilities usually provide information on what is required — see, for example, The National Archives’ ‘Technical settings’ page for its document service at <www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documentsonline/help/help-technical.asp> — and you should normally see a warning if some required facility is absent from your configuration.

The main features which cause problems are:

A ‘cookie’ is a piece of information a website stores on your hard disk for its own future use. This is how a site can ‘remember’ who you are from one visit to the next. However, browsers can be configured to reject cookies, and some people do this to preserve their internet privacy. This will make pay-per-view sites and online shops unusable — in fact any site that requires some sort of login will only work with cookies enabled. If you are concerned about cookies, you can configure your browser to accept only those sites you specify. The online help for your browser should tell you how to check whether cookies are enabled. Most sites that require cookies will also give instructions.

This is a scripting language which, among other things, makes it possible for a web page to validate what the user enters in an online form (checking, for example, that you haven’t left some crucial field blank) before the information is submitted. You will be unable to use sites that require this if JavaScript is disabled. The online help for your browser should tell you how to check whether JavaScript is enabled, and how to ensure it is. Most sites that require it will also give instructions.

Java is a programming language which allows programs (called ‘applets’, i.e. small applications) to run on any type of computer as long as it has software installed which can understand the language. This allows for programmable websites. Java facilities (referred to as a ‘Java virtual machine’) are normally installed and enabled automatically when you install a new browser, but can be disabled. Individual websites download their own applets to your machine — you will often see a grey box saying ‘loading’ in the browser window while an applet is being downloaded. The online help for your browser should tell you how to check whether Java is enabled, and how to ensure it is.